OpenAI Scholars: Last Steps - A Seizure Prediction Project

This is a description of my OpenAI Scholars Project. I would love to hear any feedback you may have. Enjoy!

Abstract

Epilepsy is an important problem, affecting nearly 1% of people. The fact that most people with epilepsy cannot predict an upcoming seizure can give rise to anxiety, as well as physical injuries from seizure-related accidents. Being able to predict seizures, and warn patients before they happen, can decrease the impact of these problems. It might also help with developing treatments, such as brain stimulation, which depend on being able to predict the seizures.

In this project, I explored the problem of epileptic seizure prediction using deep networks. My most successful model was a ResNet18 architecture, achieving an accuracy of 0.69 on class- and subject-balanced data, and an ROC-AUC of 0.77. The corresponding metrics for a logistic regression baseline with batch normalization were 0.55 (accuracy) and 0.77 (ROC-AUC).

Moving forward, I am excited about improving our prediction accuracy using hyperparameter tuning, and varied neural network architecture and preprocessing approaches. With a performant network, I then want to move forward to interpretability methods such as activation maximization, to help us understand how the network learns and which features of the neural signal are important for predicting future seizures.

Introduction

The overarching question of my project was: Can we predict future epileptic seizures from neural time-series using deep learning applied to spectrograms of brain signal?

Importance

Epilepsy affects more than 46 million people globally (Cooper et al., 2019). Its prevalence is greater than 0.6% of the world’s population (Cooper et al., 2019; Vaughan et al., 2019), and it disproportionately affects lower-income countries (Vaughan et al., 2019). Between 20 and 40% of epileptic patients suffer from drug-resistant epilepsy (Vaughan et al., 2019).

Patients with epilepsy experience higher rates of physical injuries including drowning, head trauma, and car accidents; and mental health problems including anxiety, depression, and suicide than the general population (Tomson et al., 2004; van den Broek et al., 2004; Mahler et al., 2018; Cengiz et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). These problems can in part be attributed to the unpredictable nature of seizures (Berg et al., 2019). It has been proposed that seizure prediction devices can help reduce the secondary adverse outcomes associated with epilepsy, most notably anxiety related to upcoming seizures (Thompson et al., 2019; Chiang et al., 2020).

Some patients with drug-resistant epilepsy choose to have resective surgery, which entails removing the affected brain tissue to control their seizures. If we can improve models for seizure prediction, that could open the path to more effective closed-loop brain stimulation treatments (reviewed in Dümpelmann, 2019). This, in turn, could enable some patients with drug-resistant epilepsy - who might otherwise choose resective surgery - to retain more brain tissue while still controlling their seizures.

Tractability

In order for this project to be tractable, there needs to be a time period prior to seizure onset, a preictal state, which is distinguishable from other time periods when a seizure is not imminent, an interictal state. Although the field of seizure prediction originated more than 40 years ago (reviewed in Kuhlmann et al., 2018), two decades ago the existence of an identifiable preictal state remained a matter of debate (Lehnertz & Elger, 1998; Le Van Quyen et al., 2001; De Clercq et al., 2003; Mormann et al., 2005). Today, it is clearer that this endeavor is possible (Mormann et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2013; Kuhlmann et al., 2018). A handful of clinical trials have been attempted or are underway (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, see e.g., numbers NCT01043406, NCT03882671, NCT04061707).

A number of papers have applied deep learning to the problem of epilepsy prediction (reviewed in Rasheed et al. (2020). Several projects have been conducted using CNNs; one using an LSTM; one using a GAN; and one using DCAE and LSTM. Sensitivity ranged from about 81.2 % (0.16 false positives per h) to 99.7 % (0.004 false positives per h). The reported prediction horizon ranged between 5 minutes up to 2 h prior to seizure onset. Most reported successful prediction on the order of minutes prior to the seizure. These models are typically designed as within-subject prediction problems.

Hypothesis

It will be possible to distinguish preictal from interictal epochs using a residual neural network. Preictal epochs are those that occurred within 1 h prior to seizure onset. These are our target epochs. Interictal epochs occurred at a maximal delay from any seizure, given the constraints of the recordings. This hypothesis is consistent with the idea that the pre-seizure state is identifiable, and with past performance on the Kaggle competition associated with this dataset.

Model architecture

My main model was the residual neural network architecture (ResNet, He et al., 2015), available as a torchvision model (ResNet18). I was working with the spectrogram representation of the neural data (see ‘Method’) below, making the problem somewhat analogous to image classification, which is one of the problem spaces in which ResNets have excelled. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that a ResNet model has been applied to the problem of seizure prediction using intracranial data. As a baseline model, I used a logistic regression with batch normalization. I used the Adam optimizer in both cases.

Method

Dataset

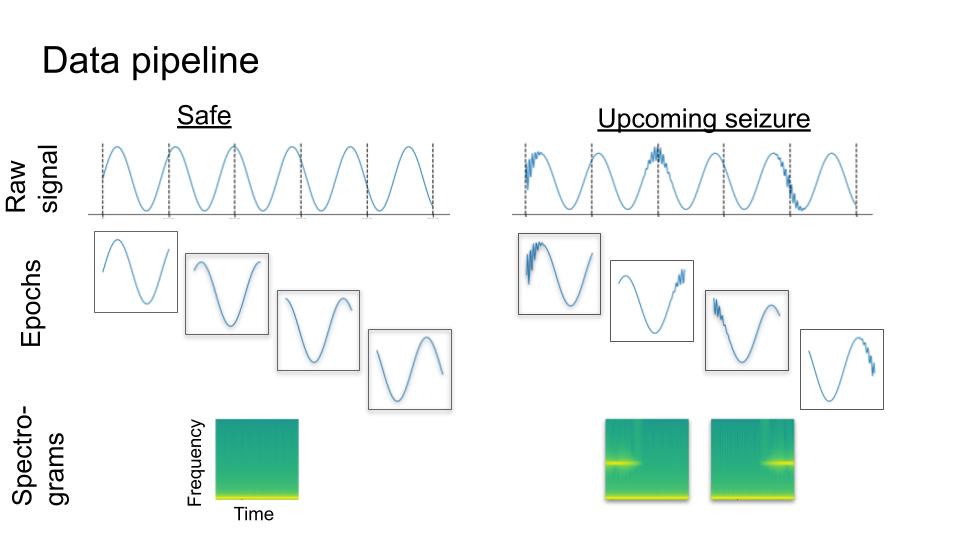

I used a publicly available epilepsy dataset provided by the American Epilepsy Society and Kaggle. The dataset consisted of intracranial recordings from N=5 dogs and N=2 human participants. For the current project, we restricted analyses to the five dogs’ data. The raw data was segmented into 10-minute epochs, each of which were labeled Preictal (target, N=265) or Interictal (non-target, N=3,674). Each epoch was a matrix of shape time x electrode. For the purposes of this project, I used the spectrogram representation of each electrode time-series separately, as an image of shape time x frequency. We used the spectrogram representation of the neural time-series (Figure 1). One motivation for using this representation is that electrical oscillations are ubiquitous in the brain, and there is a long history of studying them in neuroscience. Neural oscillations are viewed as one putative mechanism by which the brain computes (see Buzsaki, 2006). The evolution of spectral power in different frequency bands over time are best represented in spectrograms. Hence, the spectrogram can be viewed as a “natural” and appropriate representation of neural data. (A similar argument can be made for sound).

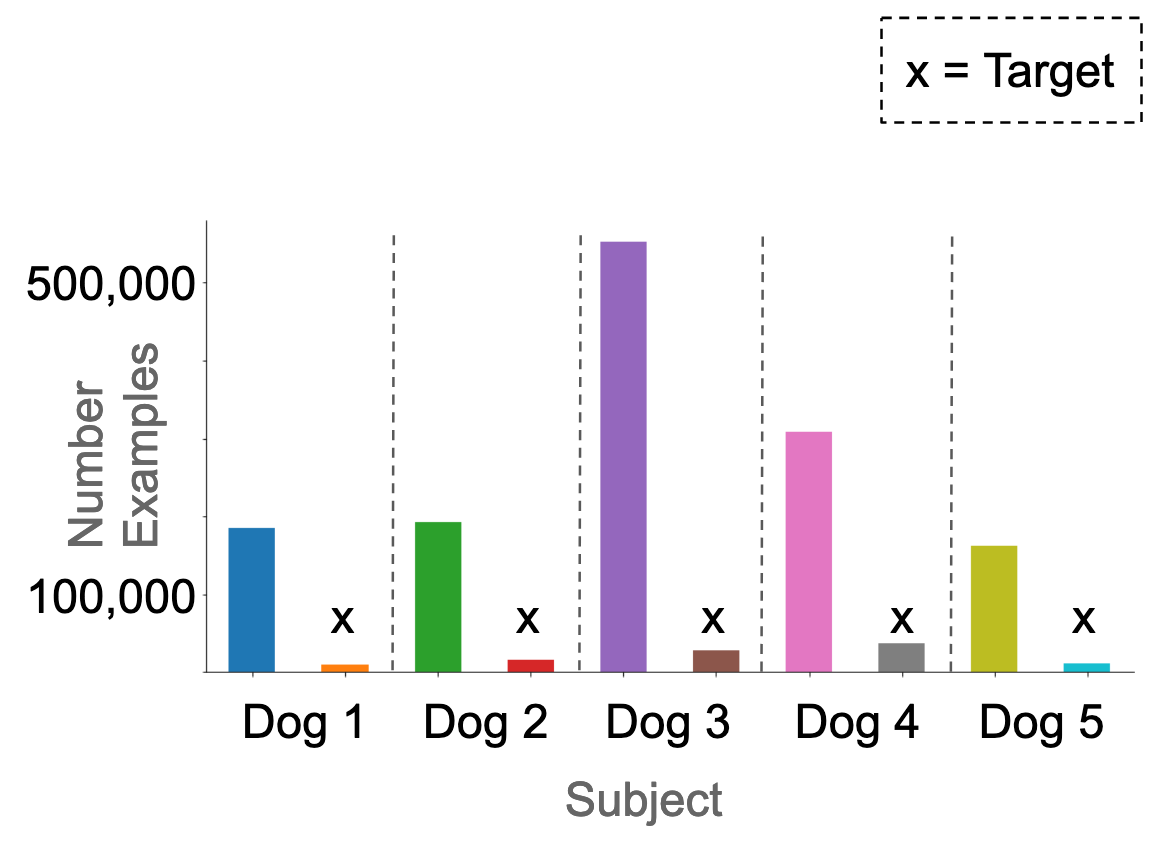

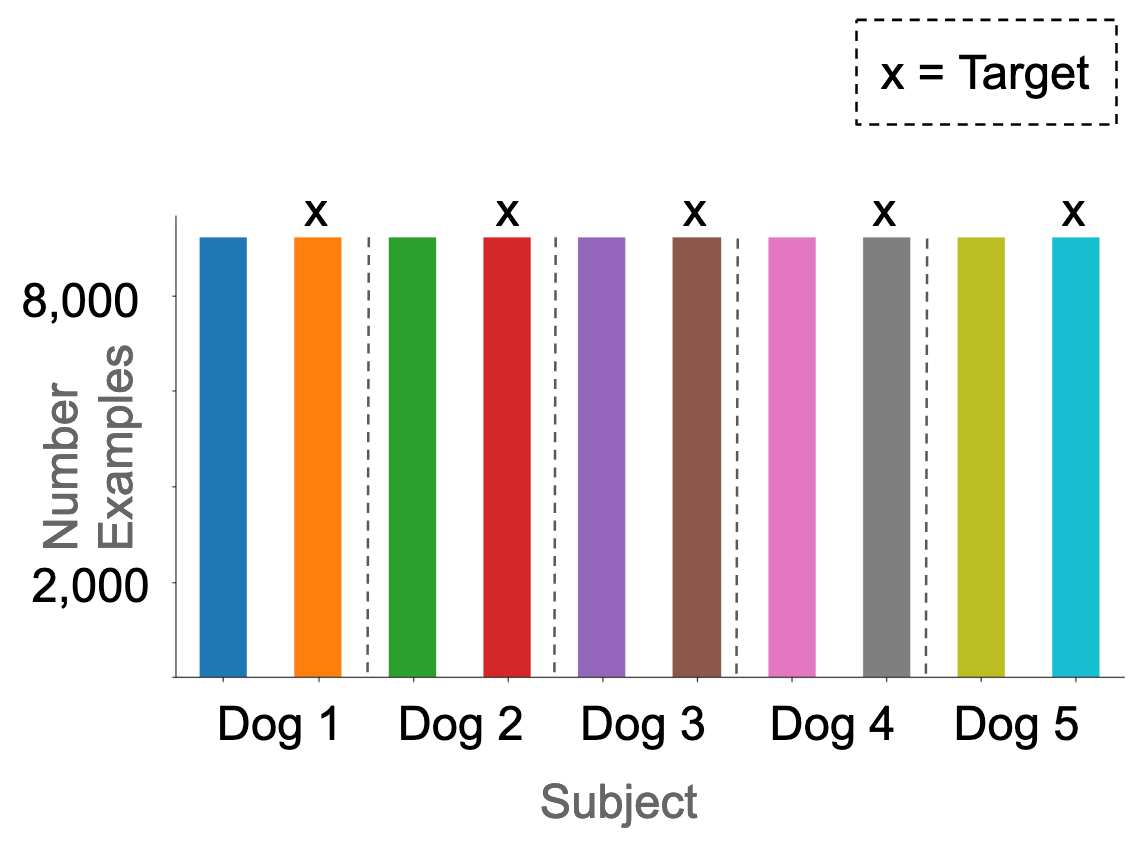

We treated each recording electrode as a separate example, because this yielded more training examples, and also allowed us to work around the fact that the number of electrodes was inconsistent between subjects. We additionally segmented each 10-minute epoch into 20-second epochs (Figure 1). This yielded 126,300 preictal, and 1,750,020 interictal examples. In total, 6.7% of the dataset were targets. In the original dataset, these were not homogeneously distributed across the subjects (Figure 2).

Results

Baseline: Logistic Regression

As a baseline model, I used a logistic regression with batch normalization. This model reached a peak accuracy level of 0.55 on the class- and subject-balanced dataset, and receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC) of 0.57, in other words a modest improvement over chance (0.5) performance.

Best Model: ResNet18

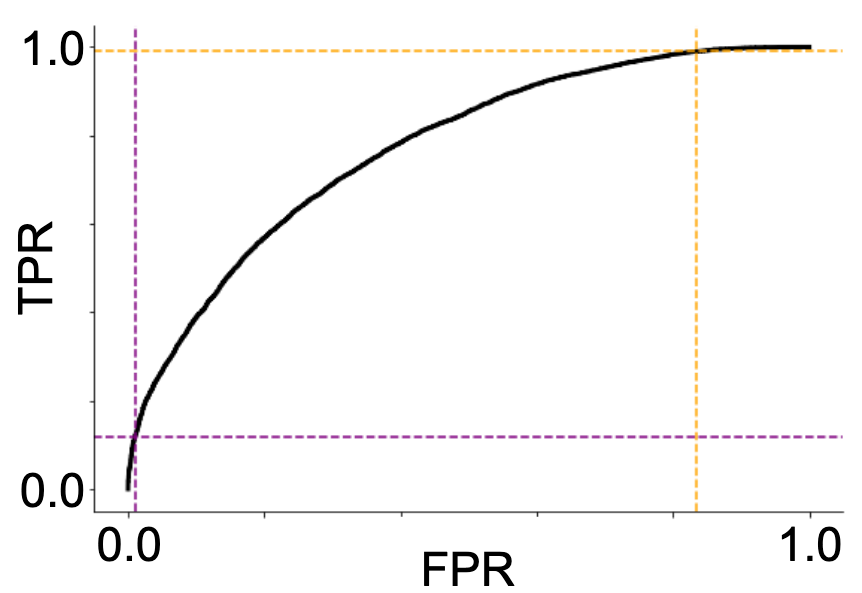

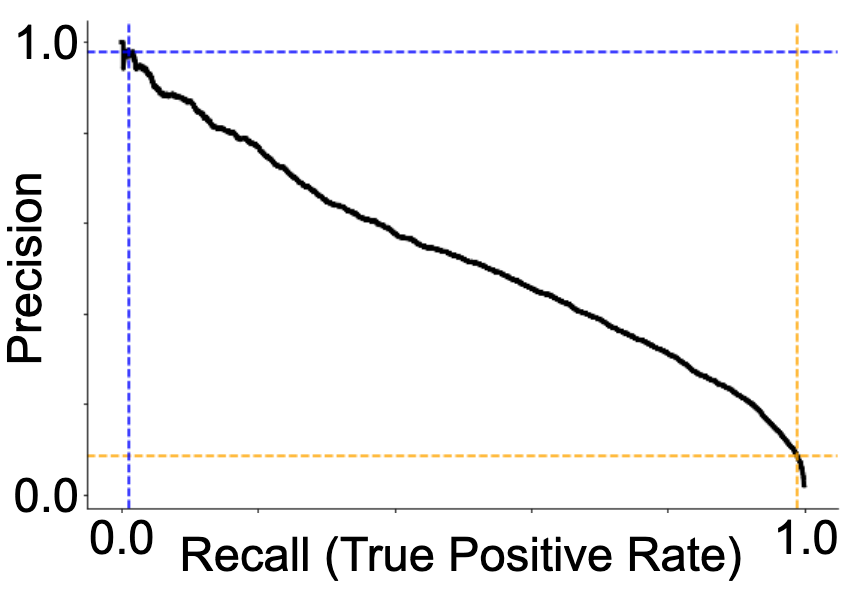

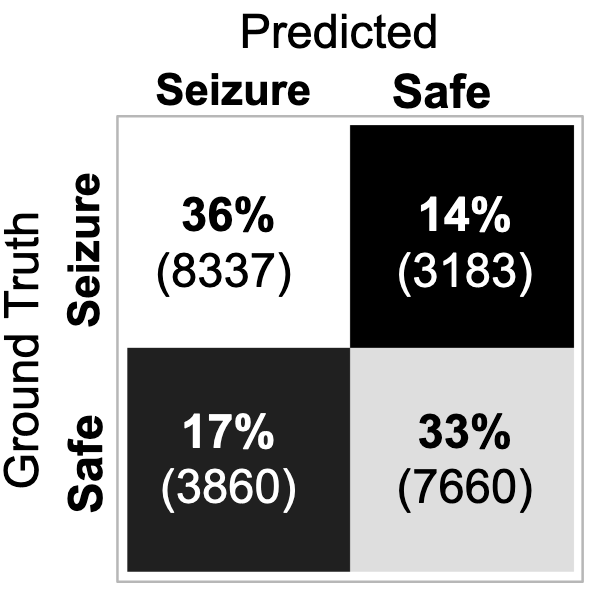

My best performing model was a ResNet18 architecture (not pre-trained). It reached an accuracy of 0.69 and ROC-AUC of 0.77. The ROC and precision-recall curves, as well as the associated confusion matrix, are presented in Figure 3. I found that the best performance was reached with a learning rate of 0.001 and batch size of 8.

Discussion

Conclusion

The early results presented here show promise for the possibility of successful seizure prediction using a ResNet model.

Limitations

One reason why we didn’t see higher accuracy with the current model as compared to, for example, previous submissions to Kaggle, is that our data was segmented into 20-second epochs and separated by electrode, as opposed to the original 10-minute epochs concatenated across electrodes in Kaggle. It is possible that the requisite “signature” of an upcoming seizure is not present in each one of these 20-second chunks and in each individual electrode. Training a second model to aggregate a common prediction out of the 20-second epochs and all electrodes belonging to the same subject, may yield higher performance.

As the duration of the seizure prediction horizon (how long before a seizure it is possible to predict it) is also a matter of debate, it is not certain that each of the 10-minute epochs labeled as “preictal” by Kaggle contain predictive features, especially those that occur early prior to seizure onset. In other words, some of the data examples labeled “target” may not in fact contain any information that would enable us to distinguish them from non-target examples.

A more practical limitation of the current project, should we reach higher predictive accuracies, is that it was conducted on intracranial data. For most epilepsy patients, only a non-invasive device would be practical, meaning that any successful model would need to be further validated on scalp EEG data. Moreover, for the purposes of device development, the tradeoffs in setting the detection threshold (illustrated in Figure 3) would need to be carefully considered. While it is critical to not miss any prospective seizures, the flip side of that coin is that too many false alarms will generate a phenomenon known as “alarm fatigue” whereby the warning signal becomes ineffective due to too many false alarms.

Future directions

Moving forward, my first priority is to improve the prediction accuracy. While I have explored the parameters learning rate, and batch size, there is more work to do in the space of hyperparameter tuning and regularization. In the space of hyperparameter tuning, I am most excited about varying the epoch duration as an immediate next step. Perhaps the requisite preictal feature is not present in 20-second chunks, but in longer chunks, or perhaps longer-range temporal correlations give away an upcoming seizure. Relatedly, restructuring the data into 3D tensors, where we would also consider the channel dimension would give the network an opportunity to learn also correlations across electrodes as they evolve over time, and these correlations may be potent predictors of epilepsy based on past research. Dropout and weight decay are two avenues for regularization that I look forward to exploring next. I also want to examine how different neural network architecture would fare on this problem, starting with larger ResNet models such as Wide ResNet, but eventually also delving into sequence models. I am further interested in exploring model performance as a function of proximity to seizure onset time. This could be done by reformulating the current model as a multi-class problem with the different epochs being separate classes. Once I have a performant model architecture, I am excited about exploring what the network has been able to learn, using interpretability methods, such as visualizing the network weights or maximizing the unit and layer activations. As a preliminary analysis, I have visualized the network weights of the first convolutional layer in our best performing ResNet model, and found that it appears to have some interesting structure including picking up on activity changes over time. The following step after that would be to use activation maximization approaches similar to this tutorial (code here). Activation maximization means that you optimize the input (rather than the weights) in order to maximize the output of a given layer or neuron of the network. This will give you a representation of what aspects of an input image a trained network “cares about” in making its classification. Activation maximization would allow us to identify frequency bands or even spectrotemporal patterns (e.g., alternating increases and decreases within a frequency band) that allow the network to distinguish between the preictal and interictal states. Ideally, some of these patterns would correspond to known features associated with onset of an epileptic seizure, e.g., spike-and-wave complexes or rapid discharges (Bartolomei et al., 2008), while others may be novel.

I look forward to continuing to work on this project, and seeing where it takes me.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my mentor Johannes for being my project advisor, pair programming tutor, and neural network debugging co-pilot for the past several months. I am extremely appreciative to OpenAI, especially Greg Brockman and Sam Altman, for the existence of the OpenAI Scholars Program - and for having had the opportunity to participate in it. I thank our program coordinators, Christina Hendrickson and Muraya Maigua, for all the work and care that they’ve poured into our program this spring. I am grateful to my fellow Scholars, Alethea, Pamela, Kamal, Jordi, Andre, and Cathy, for their authenticity, intelligence, and kindness: They have been an invaluable community to me, especially given the global events that played out this year. I thank the Clarity Team, especially Ludwig Schubert and Chris Olah, and the Reflection Team, especially Paul Christiano, for great research ideas. Finally, I thank all the awesome OpenAI folks that I met and had entertaining and educational conversations with, starting with lunches in the office, and then over virtual “donut calls”. So long, and thanks for all the donuts!

References

Bartolomei, F., Chauvel, P., & Wendling, F. (2008). Epileptogenicity of brain structures in human temporal lobe epilepsy: a quantified study from intracerebral EEG. Brain, 131(7), 1818–1830. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn111

Berg, A. T., Kaiser, K., Dixon-Salazar, T., Elliot, A., McNamara, N., Meskis, M. A., Golbeck, E., Tatachar, P., Laux, L., Raia, C., Stanley, J., Luna, A., & Rozek, C. (2019). Seizure burden in severe early-life epilepsy: Perspectives from parents. Epilepsia Open, 4(2), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12319

Buzsáki, G. Rhythms of the Brain (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2006) Cengiz, O., Atalar, A. Ç., Tekin, B., Bebek, N., Baykan, B., & Gürses, C. (2019). Impact of seizure-related injuries on quality of life. Neurological Sciences, 40(3), 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3697-3

Chiang, S., Moss, R., Patel, A. D., & Rao, V. R. (2020). Seizure detection devices and health-related quality of life: A patient- and caregiver-centered evaluation. Epilepsy & Behavior, 105, 106963. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106963

Cooper, C., GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 18(4), 357–375.

De Clercq, W., Lemmerling, P., Van Huffel, S., & Van Paesschen, W. (2003). Anticipation of epileptic seizures from standard EEG recordings. The Lancet, 361, 970–971.

Dümpelmann, M. (2019). Early seizure detection for closed loop direct neurostimulation devices in epilepsy. Journal of Neural Engineering, 16(4), 41001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab094a

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016). Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016-Decem, 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90

Kuhlmann, L., Lehnertz, K., Richardson, M. P., Schelter, B., & Zaveri, H. P. (2018). Seizure prediction — ready for a new era. Nature Reviews Neurology, 14(10), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0055-2

Lehnertz, K., & Elger, C. E. (1998). Can epileptic seizures be predicted? evidence from nonlinear time series analysis of brain electrical activity. Physical Review Letters, 80(22), 5019–5022. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.5019

Liu, X., Chen, H., & Zheng, X. (2020). Effects of seizure frequency, depression and generalized anxiety on suicidal tendency in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Research, 160, 106265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106265

Mahler, B., Carlsson, S., Andersson, T., & Tomson, T. (2018). Risk for injuries and accidents in epilepsy. Neurology, 90(9), e779 LP-e789. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005035

Mormann, F., Andrzejak, R. G., Kreuz, T., Rieke, C., David, P., Elger, C. E., & Lehnertz, K. (2003). Automated detection of a preseizure state based on a decrease in synchronization in intracranial electroencephalogram recordings from epilepsy patients. Physical Review E - Statistical Physics, Plasmas, Fluids, and Related Interdisciplinary Topics, 67(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.67.021912

Rasheed, K., Qayyum, A., Qadir, J., Sivathamboo, S., Kwan, P., Kuhlmann, L., O’Brien, T., & Razi, A. (2020). Machine Learning for Predicting Epileptic Seizures Using EEG Signals: A Review. 1–15. http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.01925

Mormann, F., Kreuz, T., Rieke, C., Andrzejak, R. G., Kraskov, A., David, P., Elger, C. E., & Lehnertz, K. (2005). On the predictability of epileptic seizures. Clinical Neurophysiology, 116(3), 569–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2004.08.025

Ruffini, G., Ibañez, D., Castellano, M., Dubreuil-Vall, L., Soria-Frisch, A., Postuma, R., Gagnon, J. F., & Montplaisir, J. (2019). Deep learning with EEG spectrograms in rapid eye movement behavior disorder. Frontiers in Neurology, 10(JUL), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00806

Selbst, A. D., & Barocas, S. (2018). The intuitive appeal of explainable machines. Fordham Law Review, 87(3), 1085–1139. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3126971

Thompson, M. E., Langer, J., & Kinfe, M. (2019). Seizure detection watch improves quality of life for adolescents and their families. Epilepsy & Behavior, 98, 188–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.028

Tomson, T., Beghi, E., Sundqvist, A., & Johannessen, S. I. (2004). Medical risks in epilepsy: a review with focus on physical injuries, mortality, traffic accidents and their prevention. Epilepsy Research, 60(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2004.05.004

van den Broek, M., Beghi, E., & Res.-1. Group (2004). Accidents in Patients with Epilepsy: Types, Circumstances, and Complications: A European Cohort Study. Epilepsia, 45(6), 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.33903.x

Le Van Quyen, M., Martinerie, J., Navarro, V., Boon, P., D’Havé, M., Adam, C., Renault, B., Varela, F., & Baulac, M. (2001). Anticipation of epileptic seizures from standard EEG recordings. The Lancet, 357(9251), 183–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03591-1

Vaughan, K. A., Ramos, C. L., Buch, V. P., Mekary, R. A., Amundson, J. R., Shah, M., Rattani, A., Dewan, M. C., & Park, K. B. (2019). An estimation of global volume of surgically treatable epilepsy based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of epilepsy. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1127–1141. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.3.JNS171722

Wang, S., Chaovalitwongse, W. A., & Wong, S. (2013). Online seizure prediction using an adaptive learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 25(12), 2854–2866. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2013.151